Can You Avoid Bogeys in the Investment Game?

by Gabriel Lewit

On its surface, it may not seem like golf and investing have much in common. After all, golf is a sport played in wide-open spaces, where most players wear funny pants and some even drink beer in the golf cart. You probably don’t deal with your investments outdoors, and you likely don’t dress funny at the same time. Most certainly you’re not drinking beer when you’re trading… are you?

When you get to know me, you will find that golf has always played a huge role in my personal and professional life. So, it should be no surprise that earlier this year I was glued to my TV for almost every shot of the 2018 Masters Tournament. If you happen to be a golf fan as well, you watched last year’s champion, Sergio Garcia place the coveted Green Jacket on the 2018 Champion, Patrick Reed. Reed’s game was extremely impressive given the pressure he must have been feeling while in contention for his first Major Championship.

Every time I watch a Major Championship golf tournament I always ask myself, “these guys are all professionals, so how did this guy (the winner) beat out everyone else?” Former professional Tommy Armour said it best when he said, “The best way to win is by making fewer bad shots”. He was absolutely right! The winner didn’t even have to make great shots all week, he just needed to avoid making terrible ones.

Everyone knows that amateurs can make a lot of bad shots, but it can happen to professionals too. Just ask Jean van de Velde about his 1999 collapse in the Open Championship or Jordan Spieth about his quadruple bogey on hole 12 at the 2016 Masters.

“The best way to win is by making fewer bad shots”

– Tommy Armour

How Does This Relate to My Money?

I bet you’re saying to yourself, “Ok Trent, we get it, you’re a golf nerd. What does this have to do with investing?” The answer to that is simple. Many investors professional and amateur alike – lose because of unforced errors or bad shots. These folks make decisions which negatively affect their investment performance. According to Charles D. Ellis, in his book “Investment Policy: How to Win the Loser’s Game”, the outcome for these investors is determined by their losing behavior and not the markets.

I recently received the 2018 SPIVA (S&P Indexed Versus Active) scorecard which points out that very few professional money managers consistently beat their benchmarks because they are competing against many other very smart and very talented money managers. Very similar to the golf professionals playing on the PGA Tour. Inevitably, they will commit an unforced error.

The Research is Clear

Remember, the evidence consistently shows, year after year, that even the most competent professional managers make mistakes and not one of them has the magic ball that would allow them to profitably exploit the mistakes of others consistently. The bottom line here is that there are too many talented participants competing in the game. They can’t beat the market because they truly are the market!

But what about the amateurs? Much like in sports, there is a large gap between the skill level of the individual investor (amateur) and the professional. The amateur usually loses even worse because their unforced errors are combined with emotional biases. Unfortunately, unlike amateur golfers, amateur investors have to compete in the same arena as the professionals at the very same time.

That leads me to my next question. “Do you think you can beat 2018 Masters Champion Patrick Reed in a round of golf?” Of course not! So why do so many amateur investors watch tv, read blogs, and surf the internet for the next self-proclaimed market beating strategy? Logically it just doesn’t make sense.

If a strategy like this actually existed, Wall Street’s largest companies would have already acquired it long before the average investor ever even knew it existed. There simply is no secret formula. It doesn’t exist and is one of the biggest unforced errors investors (professional and amateur) commit.

What Other Unforced Errors do Investors Make?

Here’s a look at what some of these unforced errors look like, that many don’t even recognize:

- Keeping too much in cash due to fears of a market meltdown

- Selling stocks because of political mood swings

- Buying a few individual stocks that will supposedly outperform

- Holding on to a stock because the tax on the gain would be so high

- Thinking that a simplistic index fund or two captures all the returns of the entire global market

- Not selling a stock due to sentimental reasons (“I inherited it from my father,” “I worked at that company for decades”)

- Getting out of the market because of some geo-political crisis

- Making any investment decision based on media stories or reports

- Thinking that you know something that everyone else doesn’t already know—especially professional money managers

- Having too much in large cap U.S. stocks, and not tilting toward small caps, value stocks, and international stocks

- Thinking that last year’s winners will continue to prevail, or that last year’s losers will continue to trail

- Over-estimating the frequency and severity of stock market declines, and under-estimating the speed and size of market recoveries

- Thinking that a round number (such as Dow 20,000) has any meaning at all

- Devoting a significant portion of a portfolio to gold because of doomsday predictions by someone—even if that someone is very smart

- Buying any investment that promises stock-market-like returns with zero risk

Leave the Emotion Out of the Equation

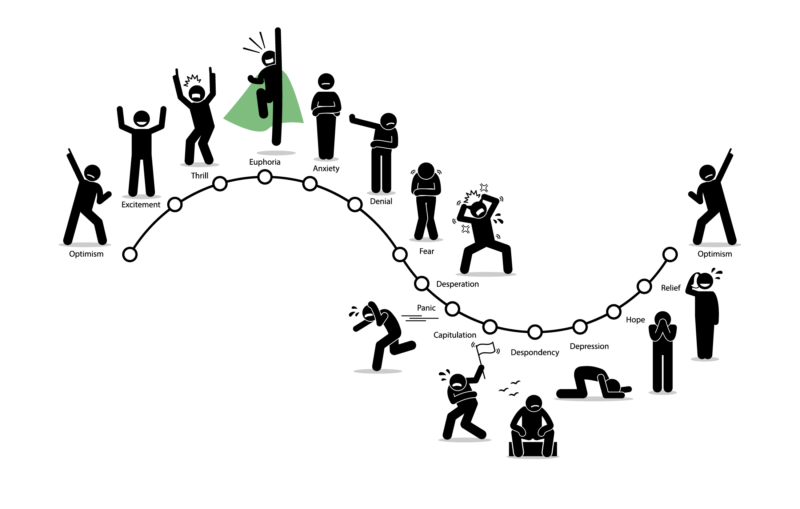

Yet year after year, amateur investors continue to make these unforced errors and continue to underperform. So, how do you avoid losing at the investment game (or making bogeys)? Stop committing unforced errors. It takes emotionally-disconnected discipline.

By “losing” we do not mean an occasional, temporary drop in the value of a portfolio. Stocks and other asset classes are volatile, and they will, of course, experience a loss from time to time. In this context, the term “losing” means underperforming. Consistently underperforming will have a serious and permanent detrimental effect on wealth accumulation and living the way you want in retirement. Consistent underperformance is a permanent loss; a temporary drop in value is, well, temporary.

Risk and return are related. However, too many investors are not receiving the return they should be receiving for the level of risk they are taking. Why? Unforced errors.

Who’s Your Caddie?

A caddie can be so much more than just someone who carries your clubs. It can be an expert to help you understand the particular hole you’re playing and the course as a whole, who can offer suggestions on the right clubs for the right shot.

In other words, if a caddie can do so much more than carry your clubs, and your advisor can do so much more than just give you buy and sell buttons, why not take advantage of their information and resources?